The houses of Virginia Woolf

by Giuseppe Bilotta

(translation by Mrs. Penny Ewles-Bergeron)

An

enthusiastic reader of Virginia Woolf, three months ago, in a Portalba bookshop,

I have the good fortune to find in my hands a book by Jean Moorcroft Wilson,

VIRGINIA WOOLF, Life and London, a biography of place, published in London in

1987 and never translated into Italian. The pale blue dust-jacket is illustrated

with a (young) profile of Virginia set against the façade of a London building.

Lower down, almost at the margin, the volume’s title ends with the note:

“with Illustrations, Maps and Guides”.

Immediately

I realise the importance of my acquisition. Full of excitement, I open it up and

realise that it is absolutely enjoyable to read. From the first to the last

page. With a simple and elegant style, the author sketches a twofold portrait of

the writer and the city of London. The prominence given to Virginia’s writing

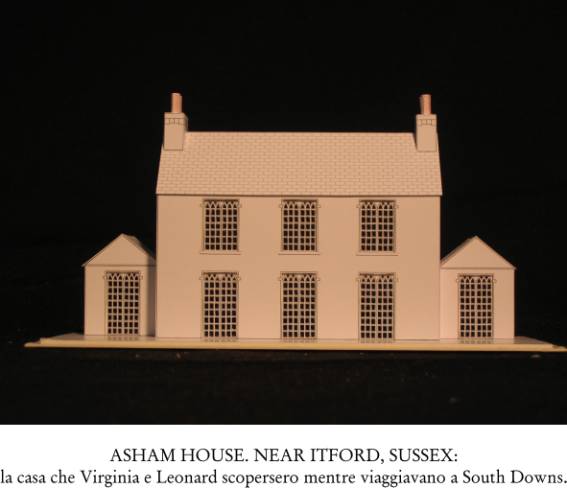

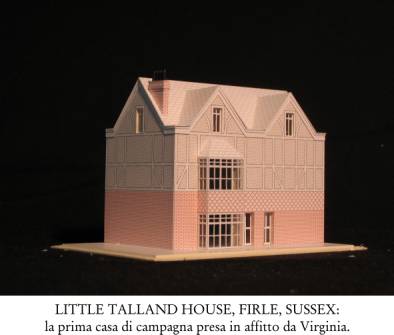

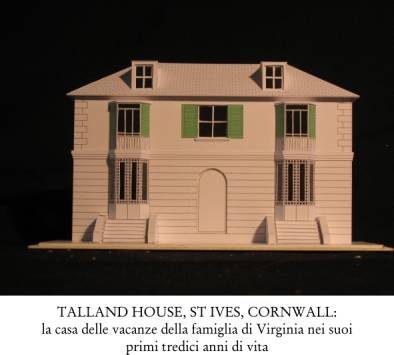

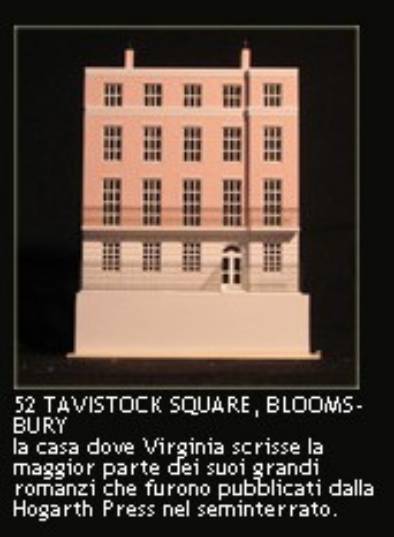

and personality is equal to that provided by the beautiful drawings of all the

houses in which Virginia lived, drawings executed by Leonard McDermid, not

without considerable difficulty. He has brilliantly reproduced the houses that

have been demolished by studying old photographs of the period.

It

is superfluous to say that McDermid’s drawings are the most striking thing in

this very beguiling book: all realistically reproduced in black and white with a

dazzling sharpness of line. The caption of each indicates either the square or

the road in the district where each house stands, the period in which Virginia

occupied it and the most notable events and works connected with it. Their scale

and vividness, at which I gaze in admiration, set in motion my own imagination.

I

imagine how Virginia and Leonard would move around the rooms of the house in

their shared routines and in various states of mind during the course of a day.

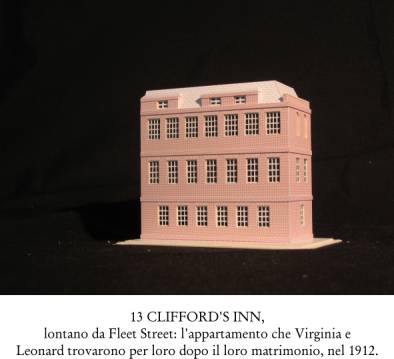

The first image is that of Virginia and Leonard, newly married, entering the

apartment at Clifford’s Inn. Once inside, looking around and touching the

walls, perhaps they thought that buildings, symbols of something sheltering and

protecting, come to life for we humans and actually possess, as Alain de Botton

has written, their own moods and their own ideas? (Personally, since I was a

child, I felt that houses, in the protective sense of the Great Mother, speak to

us and convey a specific vision of happiness.)

Once

inside the “magical” Woolfian atmosphere, I remained there a long time

daydreaming about various moments of the writer’s existence and the vitality

of London that stimulated her imagination. First of all, however, I should say

that the idea suddenly occurred to me of devising an exhibition of these houses.

It was like a bolt of lightning. As if impelled by the Virginia’s spirit that

had established contact with my own. Was it empathy? Was it a reciprocal feeling

between author and reader? Why ask myself such questions? With Virginia, an

ethereal figure, everything is possible. It’s nothing to wonder at. It accords

with the “amorous consciousness” of foscolian memory. I do not even wonder

at the fact – I admit that it was such – that the one and only copy of the

book available should have been destined for me for a long time. It was there

where I found it.

Guiseppe

Manigrasso with his sculpture, Checco Moroso with his models and the Picagallery

all allowed me to turn this empathy into a concrete reality.

I

remind all Virginia’s readers that the editor of this book is Cecil Woolf,

Virginia’s nephew.

London

London.

Like a caput mundi? No. For Virginia it is quite simply “the centre of things”.

This does not mean that it is only a commercial or social centre, but the centre

of life itself. London has for her, as Moorcroft Wilson observes,[“a mystical

meaning; it is a symbol of that which variously she calls “life”,

“truth” or “reality”, a quality which she tries to find in her own life

and transfer into her work”]. London, in fact, offers her not only the

necessary starting point for writing her books, but also a subject for them. In

her diary she writes: [“London perpetually attracts, stimulates, inspires one

to write a play, a story, a poem without the least effort, only that of moving

my legs across the street”]. The city, where the life of millions of

inhabitants converges and palpitates day and night, inhabitants with their

stories and their routines, with their hopes and their worries, with their

appearance which is always new and surprising, in the streets and square, in the

public parks, in the boats which go up and down the Thames, in the Underground,

in the red double-decker buses, is for Virginia an inexhaustible source of

amazement. [“London is a dream”] she writes in another page of the diary.

And in yet another: [“I got out and step onto a tawny yellow magic carpet and

I find myself whisked away, into the wonder, without even lifting a finger.

Nights are astonishing, with all those white porticoes and the vast silent sky.

And the people who pop in and out, lightly, pleasantly, like rabbits”].

How could one resist such a spectacle? It is wonderful and relaxing to walk

about to observe and recollect it. Perhaps to transcribe into the diary the

feelings it summons up in her. Because she walks not only to observe, but also

to think, to devise new narrative outlines, to [“break apart”] the plot.

Here she is walking along Southampton Row, passing through patches of sunlight

on the pavements, [“declaiming phrases and envisioning scenes”]. With a

broad-brimmed straw hat on her head that shades her face right down to her mouth,

she wears a beige jacket over a spotted shirt and a tweed skirt. She moves

forward with a striking manner something between fierce and drifting. As she

passes people stop and turn to look at her. What world is she from? Leonard in

his autobiography writes that the amazement she inspires in others derives from

something ethereal and inaccessible emanating from her face and distinguishing

her from other people. [“I walk composing phrases”] she writes mingling with

the crowds in Oxford Street or in Cheyne Walk, in front of Carlyle’s house,

where is it [“eternally February”].

To her friend Vita Sackville-West she describes her London walks as “reviving

fires”. A fine image that captures how urban space, with its colours and

sounds, can excite her and revive at each step her passion for London.

If on the one hand London stimulates her imagination, on the other, nonetheless,

it risks exhausting her. It can stretch her nerves to the limit. The frantic

rhythm of the great metropolis can be damaging. From the moment her health

begins to oscillate between “sanity and insanity”, an excessive stimulus can

bring about a new collapse. Thus although she longs, as a narrator and flaneuse,

[“for certain alleyways and little courtyards between Chancery Lane and the

City”], she also needs to leave London to finish another work in progress and

to be ready to sustain the enormous creative effort this requires. She goes to

the country. The refuge ready to welcome her, with the green surroundings of its

garden, is Monk’s House, at Rodmell in Sussex. Here Virginia may work in peace.

The (temporary) abandonment of a London house for a country house, a frequent

occurrence throughout Virginia’s life, is punctuated by the normal exigencies

of existence. Which, besides editorial work, is devoted to visits to friends and

relatives, attendance at receptions, theatre and concert performances, journeys

to lectures either in London, country locations or other English cities.

In such transfers the houses in London or the houses outside London, in the

context of the ‘relationship of man to universe’, constitute a living and

reviving space, a real breathing architecture, in harmony with nature’s life

forces and geometry. For this reason, beside representing a point of arrival or

departure, their importance lies in what they signified for Virginia and for us,

we who see them (from the outside) and know how much time she lived within their

walls and which works were written there. We cannot visit them, for obvious

reasons, but it is still exhilarating to step back in time, to walk through a

patch of London while Big Ben strikes the quarter hour, as in the novels Mrs

Dalloway or The Years, to mark the effects of time, to stop in front of

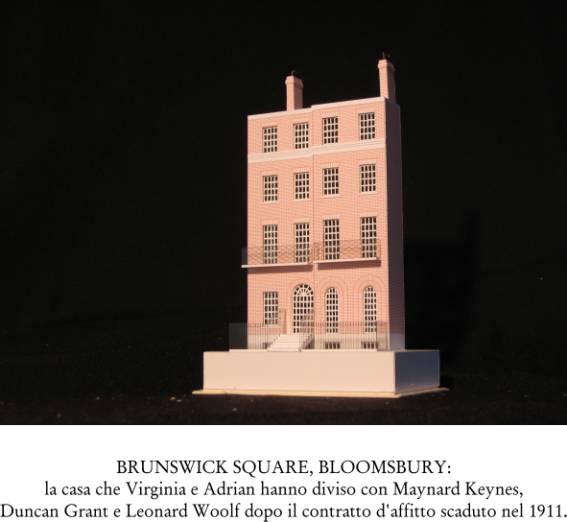

Brunswick Square, Bloomsbury, where Virginia began the first novel The Voyage

Out, and imagine we see her come out with Rupert Brooke, the young poet who died

in the war in 1915. Or in her drawing room while she entertained her other great

friend, Lytton Strachey, who [“came today for tea and was very kind, putting

up with all my criticisms of life in Cambridge and of the …ums”]: (a

reference to the group of Apostles, the Bloomsbury intellectuals amongst whom

Thoby, Adrian, Virginia and Vanessa were the main members). Many books have been

written on The Bloomsbury Group, who were destined for more than three decades

to dominate the English cultural scene, not just that of London. Amongst their

authors Quentin Bell also figured, a nephew of Virginia and also her biographer.

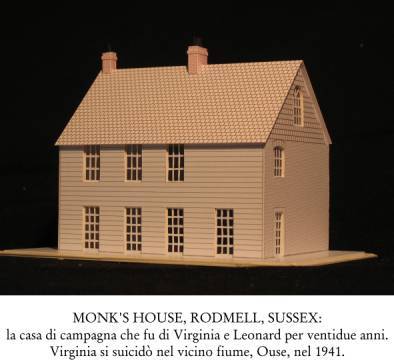

Virginia loved London very much. Perhaps she hoped to finish her days there. It

was not to be. Remembering this, one’s thoughts turn to Monk’s House at

Rodmell, where Virginia has just risen to live the last day of her life. She

will not live the whole day. Towards midday it will have ended. Remembering her

final hours and the things she did seems to me an appropriate way to bring the

London chapter to a close.

Here I am in front of Monk’s House at Rodmell. It is a clear cold March day in

1941. Virginia comes out, walks across the garden, pushes the wooden gate -

behind which an elderly Leonard, as in a photograph, leans and watches – and

she leaves for her usual walk. The last. On the table in the study, with its

view onto the garden, she has left two letters, one for Leonard and one for

Vanessa, the people she loves the most, in which she explains that she still

hears the “voices” which oppress her. Taking her walking stick with her she

heads towards the Ouse. On the riverbank she inserts a large stone into her

jacket pocket and goes to meet death: [“the only experience that I will never

describe”].

Models

by Checco Moroso

The

search for ideal beauty, a sense of form and therefore a sense of “proportion”,

are especially active and cultivated in Checco: they facilitate both his pursuit

of ideals and the realisation of projects.

This

probably explains why the models of Virginia’s houses that he has created so

splendidly have an additional quality – the power to move. Instantly. Above

all to move artists, poets and sensitive souls. The models come from the heart

and aim at the heart. Like the greatest of thoughts. It is not too much to say

that the artistry which fashioned them out of simple cardboard beautifully

coloured with rose and beige is due to a particular state of grace in which

Checco worked after he’d been both dazzled and excited by the idea of the

project. Armed with photos of Leonard McDermid’s drawings, he set to work

straight away, between July and August shaping his creations at an exhilarating

pace of work that never slackened. So here they are, in front of me, only just

completed. I look at them carefully. They are so convincing that it seems as if

Checco has produced them from his own imagination and taste without recourse to

sketches or other preparatory studies. Doubtless he kept McDermid’s drawings

close at hand for guidance as to form, but the execution of each model is down

to his own merit.

It

is clear that all the models proceed from the classical tradition (by which I

mean the important lessons of the great works of the past), arriving, without

polemical detour, at a personal synthesis of interpretation. The balance they

demonstrate between material and tone is complete. It inspires emotion. It

leaves in the eye and heart the mark of perfection. The architectural elements

vary according to order and style. Such variety does not create confusion. Quite

the opposite. It is a positive thing. In the sense that it provides a

demonstration of the creative power of comparison in the modelling of the entire

series. It beguiles the sophisticated observer at first sight and probably the

less demanding observer too. Objects possessed of beauty are infallible: nobody

can escape their siren call – the “coup de foudre” which often proceeds

from the interrelationship of elements of the whole.

Checco

is well aware of this as he adjusts the aesthetics of each model. Precisely.

Without exception. Always with the same intensity and with a sure hand. Thus he

succeeds in making each model charming whether in a group or standing alone. The

remarkable subtlety of one is equal to the remarkable subtlety of the others: it

is as if a current of energy were passing from one model to another. One’s

gaze, nevertheless, continues to roam from one to another admiring the

felicitous craftsmanship of this or that detail.

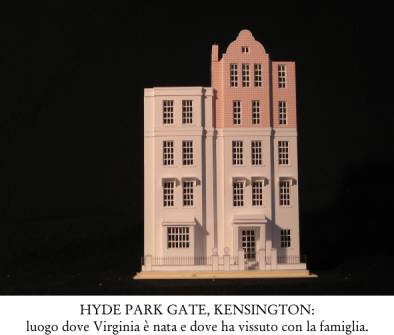

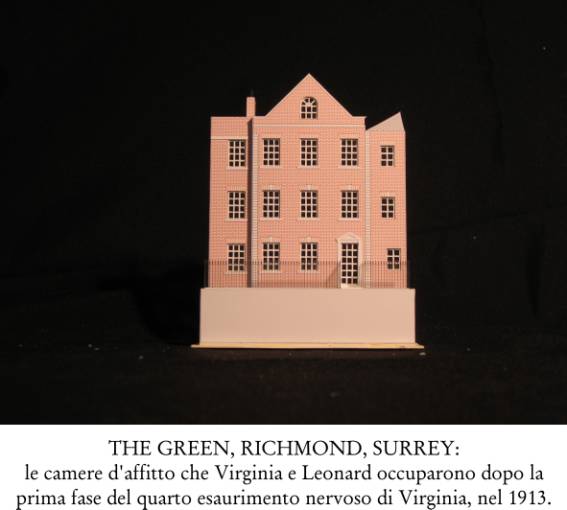

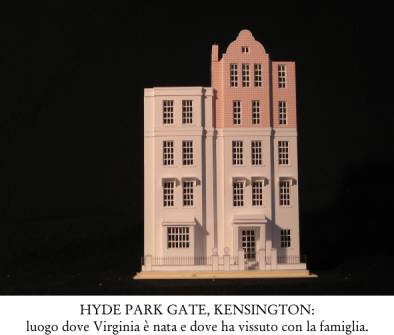

If the house in Brunswick Square, Bloomsbury, with two turrets on the roof which

look like two little watchtowers, wins one over with its eaves, its architraves,

its windows, its stanchioned balconies, its doorway with round arch and steps

and lower windows protected by a wonderfully straight and symmetrical set of

railings, the three-storey house in Clifford’s Inn with its large hinged

windows, has all the air of a convoy that has halted mysteriously in this place

to offer itself to the eye of the viewer.

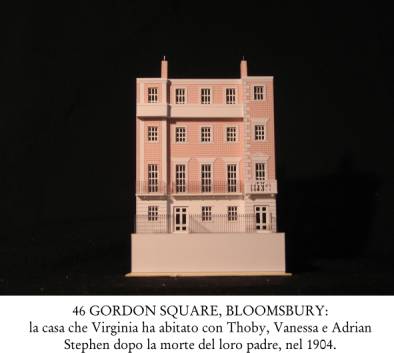

Of

the house in Gordon Square, Bloomsbury, which reminds one of a prim governess

presenting herself when called upon by the ‘Sir’ who employs her, what

strikes the viewer immediately is the balcony with parapet, balustrade, brackets,

placed on the left side of the well executed façade, just as well executed as

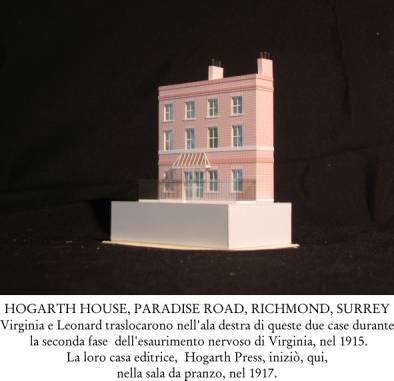

the three central balconies with railings. And what can one say of Hogarth

house? As splendid as Lady Ottoline Morrell, “who worships the arts” and is

a little left out of things, not taking part in a lively discussion between the

members of the Bloomsbury group; at Virginia’s house in Tavistock Square I am

gripped by the perfectly linear nature of the eaves, the entrance with its

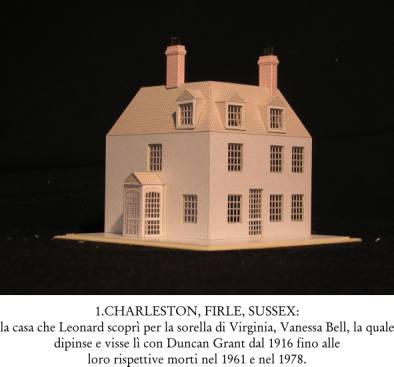

double doors, the door posts and the iron railings. Monk’s House, at Rodmell,

with its cambered roof and the clustered turrets that speak one to the other,

pleases by its structural simplicity; a typical comfortable country house, safe

and calm, a house in which to pass work and leisure time in tranquillity. The

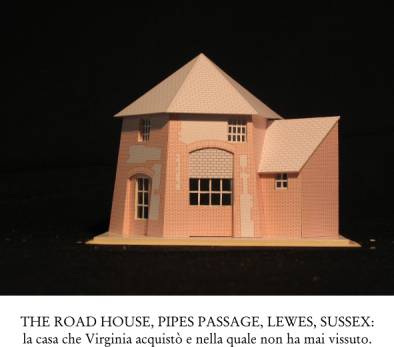

Round House, on the other hand, which seems designed to be inhabited by a fairy,

is really and truly a storybook house: tiny, pretty, with a hexagonal top and

something oriental about its outlines and its sloping roof. The external walls

are decorated with geometric elements vaguely Inca in character, while the

doorway and side windows are both designed with half arches.

For

the most part the architecture is Victorian. During the long reign of Queen

Victoria London’s urban areas witnessed enormous growth. New residential areas

sprang up. Numerous buildings were constructed throughout the urban area during

this remarkable expansion. The British Empire, which continued to flourish in

the second half of the nineteenth century, celebrated the last splendours of its

colonial power by making London greater and more beautiful.

The

houses where Virginia lived feel the effects of this Victorian atmosphere; but

their reconstruction in miniature, so to speak, resonates even more with the

pure “edifying” sentiment which Checco has impressed upon them whether with

his heart or with head. It is undeniable.

Checco’s

models remind one that habitat is the mirror and the extension not only of

Virginia’s existence, but also of our own existence anywhere in the world. In

this way they allow us to rediscover the correct relationship between our own

interior model and the surrounding environment. It’s like this. The high

definition plasticity displayed by Checco contributes to this discovery.

Insuperably. Behind which, obviously, one sees the euclidian study of form

brought gradually to perfection through time with the additional framework of

mathematics and neo-renaissance perspective. Such qualities, in the panorama of

modern architecture, assure an outstanding place for Checco’s mode of

discourse. Recognising the value of it means that by immortalising in

architecture our relationship with the cosmos, we take part in a greater work.

Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West

Virginia

and Vita meet at a dinner at Clive Bell’s home. It is the 14th December 1922.

The meeting has been arranged by Clive who, quick to see Vita’s merits, tells

Virginia that Mrs Nicolson admires her work. When Virginia has before her “the

lovely gifted aristocratic Sackville-West”, her first impression of her is

both shrewd and wise. In her diary she writes that she finds her “not much to

my severer taste – florid, moustached, parakeet-coloured, with all the supple

ease of the aristocracy, but not the wit of the artist.” Words right on the

mark: a judgement that fits like a glove. Exactly. Having clarified this, she

adds: “But could I know her?” A momentary misgiving that doesn’t exclude

the possibility of getting to know her. It is as if she is playing for time -

more to reflect on the novelty of the encounter itself than to better understand

with whom she has to do: Virginia has “seen” and understood the whole of

Vita with her x-ray vision from the very first moment.

Vita, on the other hand, is enchanted with Virginia. Four days later she invites

her to dine at Ebury Street with Clive and Desmond MacCarthy. The day after that

she writes to Virginia’s husband Harold (on a diplomatic mission in Lausanne):

“I simply adore Virginia Woolf, and so would you. You would fall quite flat

before her charm and personality. [She] is so simple: she does give the

impression of something big. She is utterly unaffected: there are no outward

ornaments – she dresses quite atrociously. At first you think she is plain;

but then a sort of spiritual beauty imposes itself on you, and you find a

fascination in watching her. She is both detached and human, silent till she

wants to say something, and then says it supremely well”. Following this

attempt to sketch a portrait psychologique, from which it is clear that the

writer wishes to study Virginia and explore her greatness, she confesses that:

“I’ve rarely taken such a fancy to anyone, and I think she likes me. At

least, she’s asked me to Richmond where she lives. Darling, I have quite lost

my heart.” The “study” of Virginia ends with an admission that she is in

love – an understanding that includes both a perception (accurate) of not

displeasing Virginia and the satisfaction of having been invited to meet her

again.

When they meet Virginia is forty and Vita thirty. Vita is already well known as

a poetess and writer. Virginia tells us that “she has finished another book -

publishes with Heinemann’s - knows everyone”. A successful author and a

fascinating woman. Quentin Bell asserts that she is a beautiful woman, “in a

lazy, majestic, rather melancholy way”. Dark eyes and a certain grace of

bearing revealed in her “an exotic strain, the blood of disreputable Spanish

gypsies”.

I do not agree with Quentin Bell. For me she is not pretty, even less is she

beautiful, judging by the photographs I’ve seen which depict her both as a

young and as a mature woman. Her face has decidedly male features. With her

short haircut and the masculine clothes she wears she is a man. Nobody is fooled.

The manner in which she sits, crosses her legs, stands and looks is virile. Her

physical presence is devoid of all traces of feminine gracefulness. Seated in

profile at her desk in her writing-room at Sissinghurst, in indoor garb, in full

maturity, it is a man who turns her gaze towards Gisele Freund as she

photographs her. Her bold and bored expression is that of a man, as are her

broad wrists and swollen ankles. Not even her hair which falls a little over her

forehead and her left cheek is enough to give her the appearance of a woman. I

see a man projecting a dull and lacklustre image. A portrait of a country

nobleman who just about deigns to listen to what a servant is telling him from

the other end of the room. Where is the much-admired allure? I do not see it.

Perhaps it was imagined or concocted by friends and admirers in the salons of

London high society?

The impression of “virility” is strikingly evident in another photograph of

her taken at the foot of the tower of her house. Dressed like an Amazon, with a

German Shepherd dog crouched by her side, her long face is even more square and

heavy-featured like a man’s; she looks like a baron who waits at the threshold

to welcome a visitor, ready to produce a suitable smile and then maintain a

frozen patrician hauteur while he guides him through an inspection of the three

hundred and sixty five rooms of Knole, drowning in silence and shadows.

Even in a photo of an Orlando 1840-style, an Orlando of many lives and many

selves, the seated Vita, with her broad-brimmed hat across her forehead, with

her bushy eyebrows and the open fingers of her left hand between her chin and

cheek, in the classical melancholic pose, is a young man which his eyes fixed on

a distant point in space. Only the flowery blouse she wears over her kilt gives

her any feminine aspect. But still her facial features, the anxious, disturbed,

estranged look in her eyes are decidedly masculine: like those of a young

businessman, dressed as a woman, ready to take part in a fancy-dress ball in

some remote country house.

Virginia too remarks on Vita’s maleness: “she is a grenadier, hard,

beautiful, virile…”. She also notes that she “displays, with apparent

unconcern, a brown down on her cheek”. However she has “a pair of

magnificent legs” and she adds: “I like her and being with her and the

splendour.” She also likes the fact that she “stalks on legs like beech

trees”. To her eyes she seems “pink glowing, grape clustered, pearl hung”.

Limpid poetic images. Almost the Song of Songs. Unequivocably. Spontaneous

outbursts of emotion oscillating between eroticism and aestheticism. To put it

more simply, the overflowings of a dawning physical attraction. It’s all here.

It’s self-evident. It counts for little that in such a state of transport

itself lies hidden “the secret of her fascination”. Without taking anything

away from everything that attracted her about Vita, it would seem all the same

that it was her legs that appealed most of all. At any rate, Vita is seen as

“a real woman”, in whom there is “some voluptuousness”. For whom she

cannot restrain herself from admitting “I like her presence and her beauty”

and then asking herself “Am I in love with her?” This first question is

followed by a second: “But what is love?” to which she does not know how to

give a satisfactory reply. Then she moves onto other thoughts and observes:

“Her being ‘in love’ […] with me, excites and flatters and interests.”

Without doubt a need for “maternal protection”, such as she already gets

from Leonard and Vanessa, enters into that interest. Having decided that she can

rely on such a feeling, she is ready to succumb to Vita’s love.

For Virginia, as has happened for millennia, love arises from the sight of

beauty. At the start everything is in the eye: the vis-à-vis between the two

writers constitutes the overture. Despite their reciprocal reserve, the two like

each other and seek each other out in order to pursue their mutual observations.

Their courtship begins with supper invitations with their respective husbands,

an exchange of books and reciprocal compliments. Their marriages are similar in

the freedom they accord to each person’s private life: Harold cultivates

homosexual affairs and Leonard has written off the sexual side of his

relationship with Virginia having discovered her frigidity.

Two years pass from first meeting to physical contact. Sexual relations can be

dated exactly: 17th December 1925 during Virginia’s visit to Long Barn. Of

this same event, on 21st December upon her return, Virginia writes in her diary:

“Vita for three days at Long Barn, from which L. and I returned yesterday.

These Sapphists love women; friendship is never untinged with amorosity”. From

the proposition that follows the first note it seems that Virginia has forgotten

her own “sapphism” which she has expressed carnally with Vita and is amazed

that lesbians’ friendship is “never untinged with amorosity”. Soon

afterwards, as if brought brusquely back to the reality of the consummated

sexual act, she gets a grip on herself and justifies herself by saying: “In

short, my fears and refrainings, my ‘impertinence’, my usual

self-consciousness in intercourse with people who mayn’t want me and so on –

were all, as L. said, sheer fudge; and partly thanks to him (he made me write) I

wound up this wounded and stricken year in great style”.

The ending “in style” of this note is, perhaps, an allusion to the beginning

of her relationship with Vita? Probably. It is uncertain. What is certain,

however, is the period of their love affair that lasts from 1925 to 1929. Their

journey to France is also a fact. They set out from Monk’s House on 24th

September 1928. Paris. Once in the French capital it is easy to imagine that

after a quick trip to the Eiffel Tower they stroll to Place de la Concorde and

from there straight to the Louvre, Room L, to admire the famous Venus de Milo,

to take luncheon at La Vigne, a bistrot dating from 1900. Follies at the Lido,

with an international supper-show and a walk along the Seine amongst the

bouquinistes - print and second-hand booksellers.

A pleasant holiday that happens to coincide with the Radclyffe Hall affair which

explodes, as Quentin Bell narrates, “six days before the publication of

Orlando and five days after Virginia had, in another manner, identified herself

with the cause of homosexuality”. Radclyffe Hall writes the novel, The Well of

Loneliness, which causes a sensation when it first appears. It is the story of a

lesbian love which now would not scandalise a soul, but which at that time in

1928 was confiscated by the police. The author was brought to court.

On the subject of which, Virginia writes in her diary that one evening she and

Morgan, who was a weekend guest at Monk’s House, got very drunk and talked

about sodomy and lesbianism. She adds that the discussion “was started by

Radclyffe Hall and her meritorious dull book”.

On her return to England, Virginia realises that those days spent in Paris in

intimacy with Vita have enriched her both personally and artistically. The

friendship has positive effects. Reinvigorated, she writes to Harold describing

as “perfect” her week with her friend and she continues “Vita was an angel

to me – looked out trains, paid tips, spoke perfect French, indulged me in

every humour, was perpetually sweet tempered, endlessly entertaining, looked

lovely”. Words which show all the warmth and satisfaction experienced by

Virginia due to Vita’s affectionate and protective manner. Undoubtedly Vita

fascinated her by her maturity, her self-assurance, her education. Elegant,

nonchalant, de belle maniere, with the international jet set style glamour of

the age. A baroness raised in Kent at Knole, one of the greatest noble houses of

England, Vita, observes Jean Dunn, “incarnated in Virginia’s eyes centuries

of English history that had made her so negligently privileged and which

surrounded her with the fascination of the past”.

Vita, on her side, as Quentin Bell also affirms, is very much in love with

Virginia. On the word “love” I would be guarded. I have the sensation,

indeed, that the ardent temperament of Vita drives her in a male way to desire

Virginia: toward physical satisfaction in bed. It is not difficult to imagine

her seduction of Virginia. Vita’s conspicuous sexuality begets ardour, being

more orientated towards the male sex than the feminine. One might say that

having worked through a phase of feminine sensuality, a male sensuality takes

over in this bisexual female conquistador who gave birth to two sons.

Much has been said on the question of sexuality, beginning with Freud’s essays

and endless publications on the subject. The prolific volume of scientific

enquiry is commendable. What has been said, however, on this matter by Karl

Kraus, who is not a sexologist by profession but merely a great writer and

polemicist, seems to me to apply to Vita. Kraus, the defender of prostitutes and

homosexuals, maintains that woman is a being who is completely sexual: whatever

thing she desires or does derives from her essential sexuality. Seen from this

perspective woman is the opposite of man. Man has sexual needs whereas woman is

sexuality. As such she experiences feeling, but is irrational. Because she’s

irrational, she cannot control her own sexual nature. Man, on the other hand, as

a rational being, can. At least potentially. Sexuality exists along a spectrum.

I do not know whether Vita reached the uncontrollable extremes of Messalina’s

sexuality. Juvenal, in powerful stanzas, describes the Roman empress on the

prowl at night seeking satisfaction in the brothels of Rome.

Such a relationship, anyway, transferred to the ideal plane of femininity and

masculinity, results in the same thing. The androgynous nature of both women,

expressed to a greater degree in one and a lesser in the other, combine

harmoniously as described by Aristophenes in Plato’s Symposium. In this

respect one can understand what impulses determine Vita’s sexuality that

represents her real nature. Virginia, who is less sensual than Vita but much

more profoundly intellectual, understands all this and adapts herself to it.

Also because the masculinity of her friend perfectly balances her own.

Such a relationship thrills Vita. Her erotic euphoria is at its peak. In the

letters she writes to Clive Bell she always speaks in admiring terms of

Virginia. For her Virginia is “more entrancing than ever” and for she who is

“incredibly lovely and fragile”, she would “go to the ends of the earth”.

Such expressions seem, nonetheless, dictated more by physical passion than pure

love, a passion that lasts only as long as its flame lasts. When the fire is

extinguished, another lover will rekindle it: as happens most regularly with

Vita.

Such was the case with Virginia. Their erotic bond becomes a friendship lasting

till Virginia’s death. Skilful in conquest as she is, Vita has no difficulty

in addressing herself to other loves. It is enough to cast one’s eyes around:

a new lover is always in sight. The high society in which she moved offered

ample choice.

Seeing her with a new lover in tow, Vanessa writes to Virginia: “I hadn’t

seen Vita for ages. She had quite simply become Orlando, but in reverse: I mean

to say that she had become a man with thick whiskers and a very authoritarian

air and, in the mix, surely something much more”. Vanessa’s observations

tally with my own: within the seductive and impressive figure of Vita hides a

man, a man called Orlando (and who never transforms back into a woman as happens

in the novel).

Virginia, however, fascinated by Vita and by their love story writes Orlando:

“a biography beginning in the year 1500 and continuing to the present day”

to celebrate the existence and the personality of her friend. The book spans

three and a half centuries and presents Vita at the beginning in boy’s apparel

only to transform her into a woman later on. Written also with bravado, bolding

letting the whole world know about her attachment to Vita. Dedicated to her, the

romance is illustrated with photographs of Vita in the attire, whether male or

female, of Orlando and bears witness both to Virginia’s love for Vita and the

incidents of her own daily life during those years. The book, for which she

“shoves everything else aside”, grows by a chapter each time Virginia

descends on Knole to see Vita and extract confessions from her about her past.

Encouraged, Vita opens up: she speaks of her romantic entanglements with

Geoffrey Scott and Violet Trefussis who in the book appears as Sasha, the

Russian princess. She provides her with all the interesting details that

Virginia needs as she drafts the work. Vita is always ready to confess and

Virginia always “closed” so as not to reveal how the work is going.

It is better not to anticipate. To get to work. Focussed in the silence of her

own writing room. The surprise will be the greater when the first copy (printed)

arrives at Knole by post from the Hogarth Press followed closely behind by

Virginia with the manuscript, her gift.